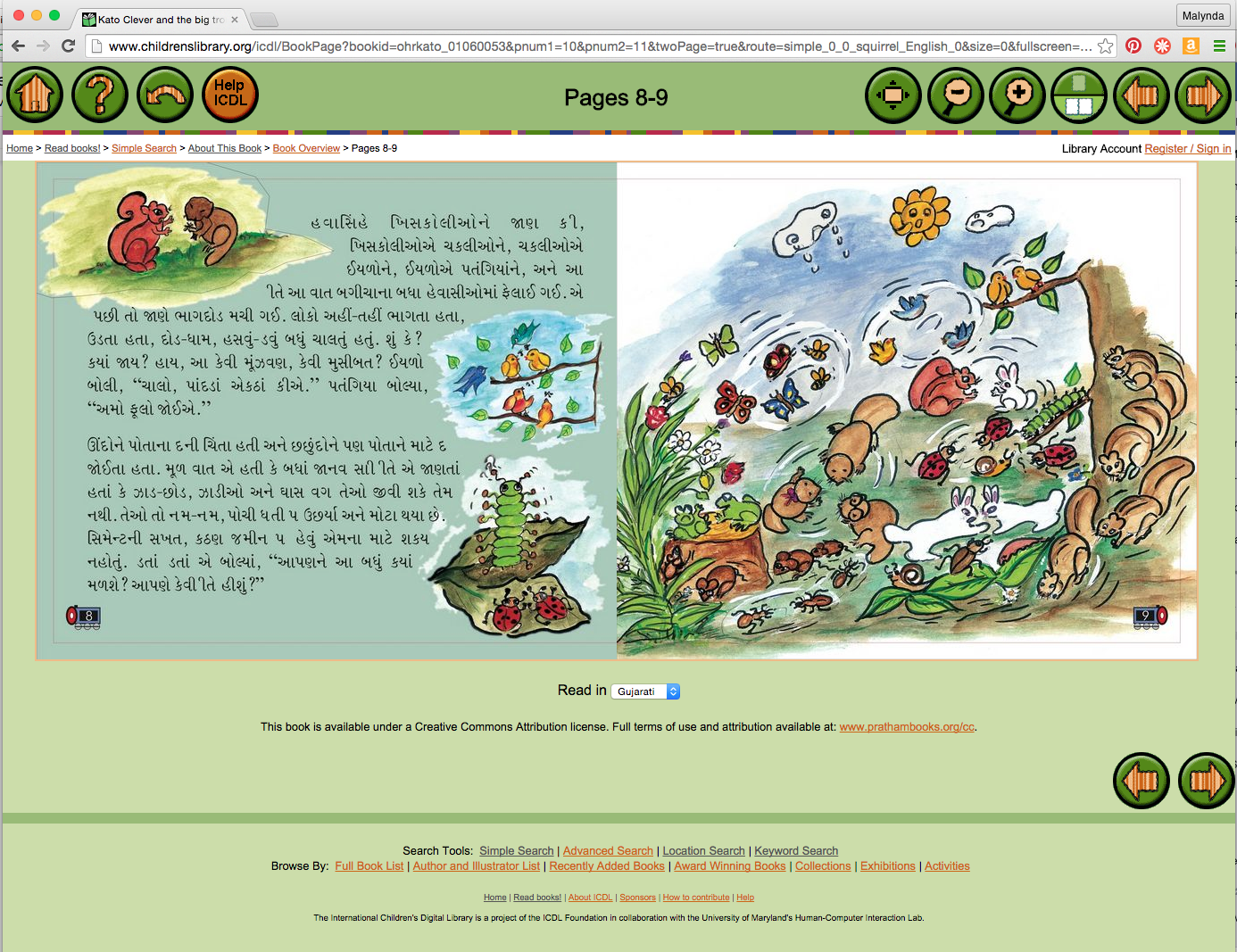

Although the project succeeds at providing digital images of the content of books for free, more books are available in languages and regions where they are less needed. Stated another way, the site provides more advantages to children who are already in more advantaged situations. The presence of effective publishing industries or non-profit sectors making high-quality books in North America, Europe, and selected Asian countries leads to a higher proportion of materials coming from these regions. The site hosts 975 books from Asia, 469 from North America, and 405 from Europe but only 103 from South America, 60 from Africa, and 53 from Australia/Oceania. Additionally, ICDL’s original goal was to provide 10,000 free books in 1000 languages. They achieved almost 50% of their goal for the number of titles, but just over 5% of their goal for the number of languages before the project’s activity declined. “Current news” postings on the website are abundant from 2002 to 2010, then drop off sharply, with the last one occurring in 2013, likely indicating that funding and interest have slowed in the last few years. The site is a useful tool as it is, but no longer seems to be growing.

Come back soon for the next post in our When Children Need Books series, which will address the African Storybook Project.

Thank you to our contributing author Megan Sutton Mercado.